Countries Argentina Topics Cities, Urban Planning, Housing, Transport Environment Local Government

Lab Latin American Bureau

BYJames Whitehead

July 28, 2022

Strong opposition to development of private luxury neighbourhoods

As Argentina slips deeper into poverty amid an economic crisis, the capital Buenos Aires has approved two major urban development projects that would transform the city’s riverside into new luxury neighbourhoods overlooking the River Plate.

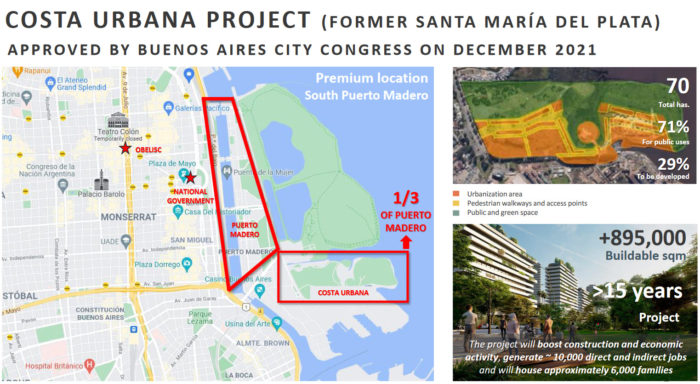

The proposals would convert 32 hectares of public land along the northern riverside, called Costa Salguero, and 71 hectares along the southern riverside, called Costa Urbana, into luxury neighbourhoods, office space and restaurants as well as feature a yacht harbor.

The projects were approved by the head of the city government, Horacio Rodríguez Larreta, from the neoliberal PRO party that has governed the capital since 2007, despite the city constitution guaranteeing free and public access to the city’s riverside.

The decision was met by criticism from residents, environmental groups, and social organizations.

Gentrification within a crisis

Argentina has been struggling with a recession-prone economy dominated by capital flight, shrinking foreign currency reserves, and spiraling inflation that is ticking along at 64 per cent yearly. The country is also weighed down by a $57 billion loan from the IMF – the largest in the lender’s history – that was taken out by former center-right president, Mauricio Macri.

The privatization of public land comes at a time when 37.3 per cent of Argentines live in poverty and the city’s housing crisis is becoming worse – shortages are concentrated mostly in the poorer southern neighbourhoods despite the majority of construction being directed towards the middle- and upper-class areas in the north.

The city government’s slogan is ‘transformation doesn’t stop’. Its large posters are plastered across the city. Yet its attempts to improve the city have neglected one of its major pressure points: the housing crisis.

‘The developments in the north and northwest are exclusively privately promoted while the production of social housing is restricted to the south of the city,’ said María Mercedes di Virgilio, a sociologist at the Gino Germani Research Institute, whose work covers gentrification, housing, and urban development.

‘Obviously, it is not enough in terms of the amount of housing that would be needed to give an effective response to the housing crisis,’ added di Virgilio. ‘Clearly this is because it is not the city government that is directing real estate development, but the private sector.’

One of the least green cities

Added to the housing crisis, one of the common casualties of urban development is green spaces. And Buenos Aires is one of the least green major cities in the world. One study found that just 9.4 per cent of the urban area is parks and public gardens, ranking it 35th out of 40 major international cities. Some of the greener cities are Oslo (68%), Sydney (46%), and Vienna (45.5%). Even the most expensive global cities provide more greenery, such as New York (27%) and London (33%).

Research on urban transformation and its consequences on working class and lower-middle class residents have mostly focused on the Global North, while overlooking similar processes at work in the Global South.

Both megaprojects in Buenos Aires were put to a public hearing between the first and second readings, where citizens and experts debated and voiced their opinions before casting a non-binding vote. They overwhelmingly rejected both projects: Costa Salguero by 97.6% and Costa Urbana by 98.3%.

Yet the city government is moving ahead with their plans to transform the riverside, without an environmental impact report or the support of the majority of its citizens.

In response to the broad criticism, the city government announced another project, BA Costa, revealing plans to recover the city’s waterfront and integrate 25km of coastal land that is accessible to the public. Many argue that it is an attempt to package separate projects (most of them that are already built) into a seemingly integrated public space in order to play down criticism.

‘For us, BA Costa it something that was put together as if it were an integral plan, which it is not,’ said María Jose Leveratto, a member of Colectivo de Arquitectas, a group of architects who oppose the privatization of the city’s coastal land.

‘If you look at the seven spaces, some of them are spaces that are already there. This is nothing new,’ added Leveratto. ‘It is put together with nice words as if to try to say that they are responding to the population’s request to have more contact with the river.’

Costa Urbana – the southern riverside project

Buenos Aires’ southern riverside lies sadly neglected at present – 71 hectares of lucrative coastal land that under the neoliberal city government promises huge rewards for the real estate industry.

The wetlands as they are today. Photo: IRSA

The wetlands as they are today. Photo: IRSAYet the land’s history should have looked very different. The original plan agreed in the 1960s was to build the world’s largest soccer stadium, with capacity of 140,000, on valuable coastal land that overlooks the River Plate. It would have been the new home for Boca Juniors, one of Argentina’s most successful soccer clubs.

The dream that promised the heights of world soccer was laid to rest by corruption, political turmoil and inflation – potent ingredients in the country’s political history.

The ex-BOCA site. Image: IRSA

The ex-BOCA site. Image: IRSAToday, the land is littered with abandoned club facilities – a cemetery of lost potential, run-down public pools, a deteriorated amusement park, and collapsed roofs.

Yet the former Boca Juniors land lies in a part of the city which is also home to Puerto Madero, with its $7,000 per sq.m. towers that squat on the riverbank, making it the most expensive neighbourhood in Latin America.

Costa Urbana map. Source: IRSA

Costa Urbana map. Source: IRSAThis elite neighbourhood was built on the banks of the River Plate and is the most isolated in the city – it’s accessible only by 5 bridges that join the island-like neighbourhood to the rest of the city.

After decades of neglect, the land was sold to IRSA, the country’s largest real estate development firm, whose thick portfolio showcases many of the most important shopping centers and commercial buildings in Argentina.

IRSA promotional video for Costa Urbana development. Video: Reporte Inmobiliairo TV, 22 December 2021.

The ex-Boca land is also located next to a 350-hectare UN-protected ecological reserve that is the city’s biggest and most biodiverse green space.

Yes the new megaproject, named Costa Urbana, was approved by the city government without any environmental impact report, and ignoring the potential threats that it poses to the city’s largest green lungs.

The proposed new neighbourhood of Costa Urbana along the southern riverside. Image courtesy of Tiempo Argentino

The proposed new neighbourhood of Costa Urbana along the southern riverside. Image courtesy of Tiempo Argentino‘A project on the scale of Costa Urbana will have an enormous urban and environmental impact,’ said Leveratto. It has consequences ‘in terms of infrastructure requirements for services, traffic, and transport needed to make this project viable as well as on the capacity for rainwater retention and runoff, the drainage of groundwater, and the microclimate in general.’

A law of the wetlands

Environmental activists and groups have been pushing for a Law of the Wetlands, in which specific land would be preserved to absorb carbon dioxide, helping to mitigate the effects of climate change as well as flooding – by absorbing water from the river. The law has been swirling around congress for years, being passed between the Senate and the lower house while more coastal land gets purchased by property developers, with the environmental impact from these projects remaining unknown.

‘These impacts have not yet been analyzed or assessed,’ added Leveratto, ‘and will affect the ecological reserve, the city in general, and the Rodrigo Bueno neighbourhood in particular.’

The towers of Costa Urbana would overshadow Rodrigo Bueno, a vulnerable and informal settlement of more than 2,500 people, separated from the ex-Boca Juniors land by a thin channel of water.

The Supreme Court of Justice ordered the city government to formally urbanize and integrate Rodrigo Bueno into the rest of the city, thus protecting a settlement that had been neglected for decades by a government that also attempted to evict its residents multiple times.

However, formalizing precarious neighbourhoods and relocating their residents to new housing complexes on valuable coastal land expose them to risks of gentrification that would eventually push them out.

‘Processes of gentrification in the city, until now, have not been developed in informal neighbourhoods,’ said di Virgilio. ‘Yet currently there is a risk that they will begin to develop in Rodrigo Bueno. It’s a neighbourhood located on the banks of the River Plate and is part of a more general process of transformation of the riverside that expresses a very strong risk of gentrification for this informal neighbourhood.’

Costa Salguero – the northern riverside project

Leave the southern riverside and drive 6 miles northwest and you’ll reach the northern riverside area of Costa Salguero.

Costa Salguero site. Image: Google maps

Costa Salguero site. Image: Google maps The planned Costa Salguero development site. Image: Ambito

The planned Costa Salguero development site. Image: AmbitoThe current site is occupied by sports facilities and a convention center, with public access to the river restricted. The new plans would sell off the public land to a private developer who would convert it into mixed use luxury buildings – houses, offices, and hotels – as well as a park.

City residents have expressed their rejection of the city coastline proposals. ‘We already have one Puerto Madero, where parks are packed with people and restaurants are half-empty,’ said Guilad Gonen, a local resident. ‘It’s the kind of place where in order to sit down or to play soccer with your kids you have to break into a luxurious neighbourhood.’

Protests and polemic caused by decision of Buenos Aires legislature to approve construction of luxury homes and offices across a large swathe of Costa Salguero. Video: DW Español, 23 October 2020

Despite the city giving the green light to the privatization and enclosure of coastal land, resistance remains strong among residents and opposition groups. ‘The city of Buenos Aires is undergoing complex structural changes that go against the grain of the common good, sustainability, and social and urban integration,’ said Leveratto.

‘But thanks to its majority in the Buenos Aires legislature, the executive power moves forward with urban planning projects and agreements without political consensus, without real participation, and without taking into account the real needs and priorities of its inhabitants.’

Rather than creating a city democratically, Buenos Aires is securing the city for private profit and in the process, pushing residents out of their own neighbourhoods.

A landscape of cement, ostentation and consumption

‘Both the proposals developed for Costa Urbana and Costa Salguero define projects where parks are diluted and intermingled with commercial promenades, offices, and housing, finally forming a landscape of cement, ostentation, and consumption,’ said Leveratto.

This is not the only way to make a city. ‘As trends in sustainable and resilient urbanism show,’ she added, ‘increasing the provision of public spaces and green areas is a much more socially equitable and environmentally sustainable way of making a city.’

A citizen-led alternative

Popular resistance to the privatization of coastal land was channeled into collecting signatures for a citizens’ initiative: the creation of a public park in Costa Salguero that is free and accessible for all.

Gathering signatures for a public park in Costa Salguero. Video: PJCiudad, 12 July 2021

In Buenos Aires, if an initiative gets at least 37,000 signatures, it forces the city’s legislature to discuss and vote on it. The public park initiative was submitted in May with over 50,000 signatures.

‘It is the first time that a citizens’ initiative has reached the requirements and will go to the legislature,’ said Leveratto, ‘the first time that an act of direct participation has led to an initiative being discussed in the legislature.’

Despite reaching a landmark in terms of popular action, expectations of the initiative being passed, scuppering real estate development along the northern coastline, are low.

‘On the day that the public park initiative was approved, that was when the city government decided to publicize its BA Costa project. It seems to me that they are trying to cover up our demand, to try to make it invisible,’ she added.

‘The truth is that since it was submitted, we have not heard anything. We have little hope that this bill will become law because the legislature has a ruling majority,’ said Leveratto. ‘But we do think that when they have to deal with it, and with us making enough noise during that moment, at least this will have a political cost, that not having paid attention to what the citizens ask for, it will have a cost in terms of their credibility before society.’